Meet the Maker: Pooja Singhal

Revivalist, curator, collector and cultural entrepreneur, Pooja Singhal, founder of atelier Pichvai Tradition and Beyond, is the curator of our Winter Exhibition: ‘Evoking Nature and Divinity.’

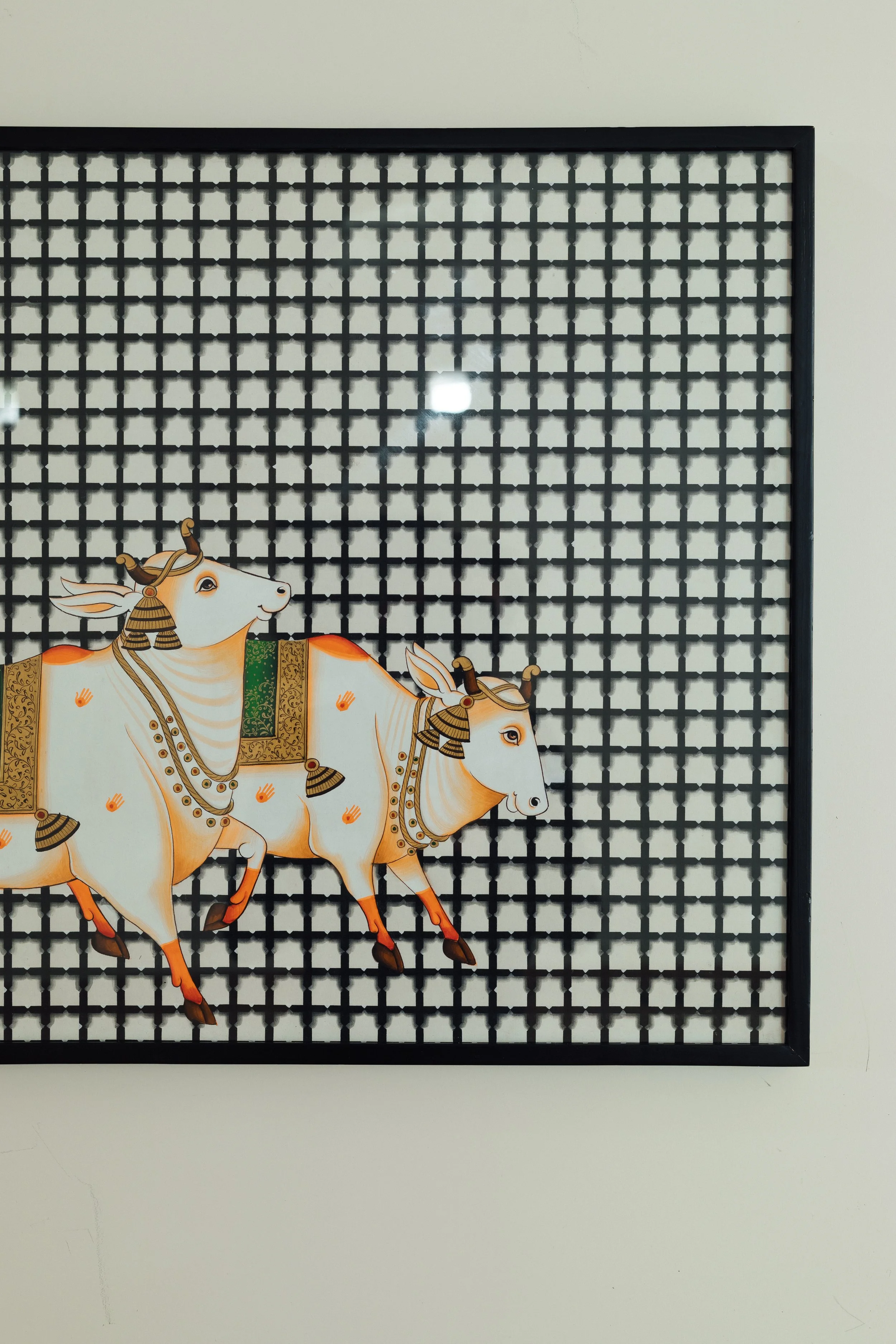

Traditionally created as backdrops in temples of Lord Shrinathji, pichwai artwork embodies devotion and storytelling, blending detailed iconography with rich textile traditions. Pooja’s work has been instrumental in the revival of pichwai painting, supporting artists in Rajasthan while presenting this legacy to global audiences.

How did your personal interest in art lead to founding Pichvai Tradition & Beyond?]

The short version to this is that art found me long before I framed the words to define my role. I grew up surrounded by craft and heritage - my mother collected artworks, artisans visited our home, and from a young age I absorbed the rhythms of making, devotion and tradition.

My academic training gave me the language of strategy, and the value of networks, but what it lacked was heart. The turning point came when I realised that a beautiful object alone was not sufficient, unless the people who made it and the rituals behind it survived.

I began to collect pichwai paintings almost instinctively. I was drawn to their luminous quality, the fact that they were both sacred and visually rich. What troubled me was their marginalisation, where these paintings that are rooted in the 17th-century temple tradition of Nathdwara, were increasingly treated as souvenirs or decorative objects alone.

So in 2015 (though the concept had been gestating earlier) I founded my atelier to create a structure that could enable revival, research, reinterpretation and sustainability.

By ‘revivalist’, I mean returning to the spirit and craft of the tradition, using mineral pigments and natural materials, and by ‘curator’, I mean shaping narratives around pichwai works, their context and display within the contemporary art world. I define myself as a ‘cultural entrepreneur’, as a steward of the art form and the building of the ecosystem so that the artists, their families and their techniques can all continue to thrive. The latter, in practice meant collaborating with master artisans as well as inviting younger artists into the atelier, re-imagining colour palettes and formats to reach contemporary collectors, while retaining the sacred DNA of the form. All of this is a continuation of something already alive that needed a new life-breath. My personal interest was the spark, but the work has become collective.

2. Pichwai painting originated in the 17th Century as a devotional art form in temples. Can you tell us a little more about it?

Pichwai painting emerged in the 17th century in the temple town of Nathdwara, Rajasthan, within the Vaishnavite Pushtimarga tradition founded by Saint Vallabhacharya - a devotional path that honours Lord Krishna through seva (service), expressed in raag (devotional music), bhog (food offerings), and shringar (adornment).

The art form took shape as a visual expression of faith, created for the worship of Shrinathji, a cherubic manifestation of Lord Krishna. The word pichwai has Sanskrit roots, with pichh, meaning ‘back’, and wai, meaning ‘hanging’, describing the artistic textile backdrops that adorned the sanctum behind the deity.

Each artwork mirrored the rhythm of the temple - the festivals, the seasons, adornments and rituals. In its early years, a few artists were permitted into the sanctum during brief darshans (sacred glimpses) to observe the deity and later recreate those moments in paint. This practice grew into a close-knit community in the Chitrakaron ki Galli, (the lane of painters) in Nathdwara, where families continue to work across generations.

A traditional pichwai is made on cotton-silk fabric prepared with khadia, a white chalk paste mixed with natural adhesives to create a smooth, absorbent surface that enhances pigment adhesion and gives the pichwai its muted earthy hues. Pigments are hand-ground from minerals like lapis lazuli and emerald, and outlines are drawn with brushes made from squirrel hair tied to bamboo. The final likhai - fine linear detailing - adds definition and depth, bringing the intricate details to life. What draws me to this tradition is the union of faith, craft and my passion for art. A pichwai is an act of offering that transforms devotion into form.

3. At your atelier in Kishangarh, you’ve shifted from traditional guru-shishya models to a collaborative studio, employing and training younger artists. What have you discovered in this process?

At the atelier in Kishangarh, I wanted to create an environment where tradition and experimentation coexist without hierarchy. The classical guru-shishya model was built on reverence and discipline, yet it often confined younger artists to imitation. What I have tried to establish instead is an open and exploratory space where the rigour of tradition sits alongside a steady circulation of ideas, and where each practitioner has the freedom to rethink the language of the form and develop fresh interpretations shaped by the direction of the work we undertake together, without being held strictly to inherited methods.

The atelier brings together artists not from Nathdwara but largely from Kishangarh and nearby regions, as finding painters from the traditional father–son lineage of Chitrakaron ki Gali has become increasingly difficult. Many younger members of that community have stepped away from the practice and no longer hold the required skill set, which made this shift necessary. The atelier serves as a place for both production and study. Artists develop new works, revisit older compositions, and document the shifts in pigment, proportion and form, extending the visual vocabulary of pichwai art. Over time, painters trained in the pichwai tradition have worked alongside miniature artists in the atelier, allowing techniques to move fluidly across practices. The clarity of line and delicacy of brushwork that define miniature painting now inform the wider studio, influencing the artists within it, and creating an exchange that continues to deepen the studio’s visual language.

Atelier Pichvai Tradition & Beyond also functions as a living archive, encouraging experimentation with scale, format and surface. Series such as the Greyscale studies and geometric compositions have grown from this shared habit of probing the tradition, rather than replicating it. This process has reshaped ideas of authorship, with a single pichwai artwork carrying the imprint of several hands and sensibilities, aligned in purpose.

4. What is your favourite piece of artwork from the collection in the Tithe Barn at Thyme?

My favourite piece in the exhibition is the peacock work, ‘Mor Raas’ - it is beautiful in the way it redefines the traditional form of the peacock, giving it a more geometric, contemporary interpretation. The colours evoke the warmth and elegance of an old English home, a gentle, universal palette that marks a refreshing departure from the conventional tones typically associated with pichwai painting. This subtle English sensibility is what makes the work stand out so distinctly.

5. You’ve said that art, motherhood and heritage all inform one another in your life. What do you hope the next generation will take away from your work?

My hope for the next generation is that they recognise how much strength lies in the lineages we inherit. We are all rooted in tradition, in our past and in our history. Our cultural heritage gives us a foundation that keeps us steady, and I cannot emphasise enough how vital it is to remain connected to that source. At the same time, my own life has shown me that tradition asks to be engaged with, not followed unquestioningly. I have lived through the parts that nurture and the parts that confine, and I have had to step past what held me back in order to grow.

What I hope the next generation carries with them is the ability to embrace the new while staying attentive to the richness of our history, art and culture. When these two aspects of life speak to each other rather than sit apart, there is room for a way of living that feels complete and fulfilling.